Basic Usage¶

What is Reinforcement Learning?¶

Before diving into Gymnasium, let’s understand what we’re trying to achieve. Reinforcement learning is like teaching through trial and error - an agent learns by trying actions, receiving feedback (rewards), and gradually improving its behavior. Think of training a pet with treats, learning to ride a bike through practice, or mastering a video game by playing it repeatedly.

The key insight is that we don’t tell the agent exactly what to do. Instead, we create an environment where it can experiment safely and learn from the consequences of its actions.

Why Gymnasium?¶

Whether you want to train an agent to play games, control robots, or optimize trading strategies, Gymnasium gives you the tools to build and test your ideas.

At its heart, Gymnasium provides an API (application programming interface) for all single agent reinforcement learning environments, with implementations of common environments: cartpole, pendulum, mountain-car, mujoco, atari, and more. This page will outline the basics of how to use Gymnasium including its four key functions: make(), Env.reset(), Env.step() and Env.render().

At the core of Gymnasium is Env, a high-level python class representing a markov decision process (MDP) from reinforcement learning theory (note: this is not a perfect reconstruction, missing several components of MDPs). The class provides users the ability to start new episodes, take actions and visualize the agent’s current state. Alongside Env, Wrapper are provided to help augment / modify the environment, in particular, the agent observations, rewards and actions taken.

Initializing Environments¶

Initializing environments is very easy in Gymnasium and can be done via the make() function:

import gymnasium as gym

# Create a simple environment perfect for beginners

env = gym.make('CartPole-v1')

# The CartPole environment: balance a pole on a moving cart

# - Simple but not trivial

# - Fast training

# - Clear success/failure criteria

This function will return an Env for users to interact with. To see all environments you can create, use pprint_registry(). Furthermore, make() provides a number of additional arguments for specifying keywords to the environment, adding more or less wrappers, etc. See make() for more information.

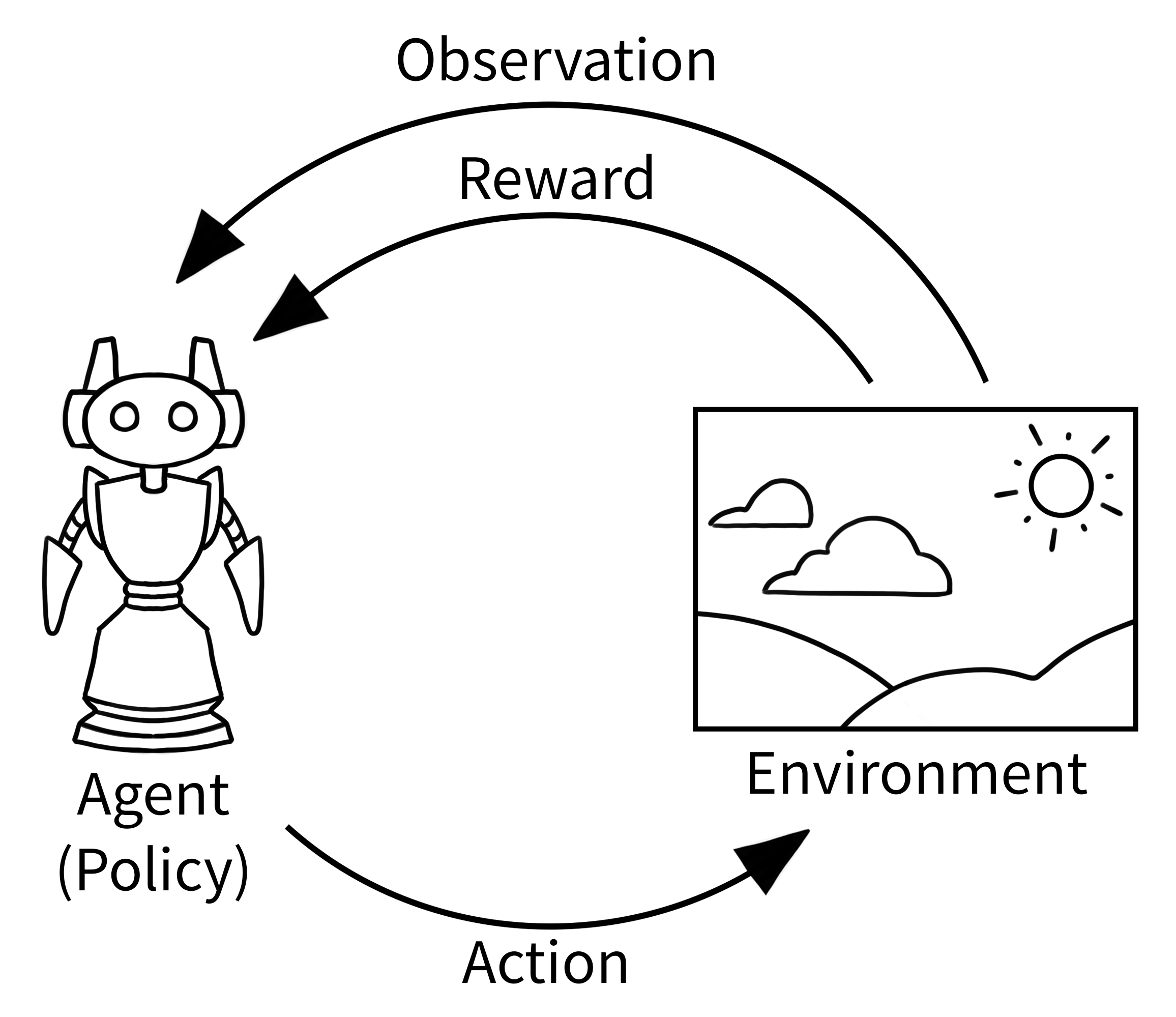

Understanding the Agent-Environment Loop¶

In reinforcement learning, the classic “agent-environment loop” pictured below represents how learning happens in RL. It’s simpler than it might first appear:

Agent observes the current situation (like looking at a game screen)

Agent chooses an action based on what it sees (like pressing a button)

Environment responds with a new situation and a reward (game state changes, score updates)

Repeat until the episode ends

This might seem simple, but it’s how agents learn everything from playing chess to controlling robots to optimizing business processes.

Your First RL Program¶

Let’s start with a simple example using CartPole - perfect for understanding the basics:

# Run `pip install "gymnasium[classic-control]"` for this example.

import gymnasium as gym

# Create our training environment - a cart with a pole that needs balancing

env = gym.make("CartPole-v1", render_mode="human")

# Reset environment to start a new episode

observation, info = env.reset()

# observation: what the agent can "see" - cart position, velocity, pole angle, etc.

# info: extra debugging information (usually not needed for basic learning)

print(f"Starting observation: {observation}")

# Example output: [ 0.01234567 -0.00987654 0.02345678 0.01456789]

# [cart_position, cart_velocity, pole_angle, pole_angular_velocity]

episode_over = False

total_reward = 0

while not episode_over:

# Choose an action: 0 = push cart left, 1 = push cart right

action = env.action_space.sample() # Random action for now - real agents will be smarter!

# Take the action and see what happens

observation, reward, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(action)

# reward: +1 for each step the pole stays upright

# terminated: True if pole falls too far (agent failed)

# truncated: True if we hit the time limit (500 steps)

total_reward += reward

episode_over = terminated or truncated

print(f"Episode finished! Total reward: {total_reward}")

env.close()

What you should see: A window opens showing a cart with a pole. The cart moves randomly left and right, and the pole eventually falls over. This is expected - the agent is acting randomly!

Explaining the Code Step by Step¶

First, an environment is created using make() with an optional "render_mode" parameter that specifies how the environment should be visualized. See Env.render() for details on different render modes. The render mode determines whether you see a visual window (“human”), get image arrays (“rgb_array”), or run without visuals (None - fastest for training).

After initializing the environment, we Env.reset() the environment to get the first observation along with additional information. This is like starting a new game or episode. For initializing the environment with a particular random seed or options (see the environment documentation for possible values) use the seed or options parameters with reset().

As we want to continue the agent-environment loop until the environment ends (which happens in an unknown number of timesteps), we define episode_over as a variable to control our while loop.

Next, the agent performs an action in the environment. Env.step() executes the selected action (in our example, random with env.action_space.sample()) to update the environment. This action can be imagined as moving a robot, pressing a button on a game controller, or making a trading decision. As a result, the agent receives a new observation from the updated environment along with a reward for taking the action. This reward could be positive for good actions (like successfully balancing the pole) or negative for bad actions (like letting the pole fall). One such action-observation exchange is called a timestep.

However, after some timesteps, the environment may end - this is called the terminal state. For instance, the robot may have crashed, or succeeded in completing a task, or we may want to stop after a fixed number of timesteps. In Gymnasium, if the environment has terminated due to the task being completed or failed, this is returned by step() as terminated=True. If we want the environment to end after a fixed number of timesteps (like a time limit), the environment issues a truncated=True signal. If either terminated or truncated are True, we end the episode. In most cases, you’ll want to restart the environment with env.reset() to begin a new episode.

Action and observation spaces¶

Every environment specifies the format of valid actions and observations with the action_space and observation_space attributes. This is helpful for knowing both the expected input and output of the environment, as all valid actions and observations should be contained within their respective spaces. In the example above, we sampled random actions via env.action_space.sample() instead of using an intelligent agent policy that maps observations to actions (which is what you’ll learn to build).

Understanding these spaces is crucial for building agents: - Action Space: What can your agent do? (discrete choices, continuous values, etc.) - Observation Space: What can your agent see? (images, numbers, structured data, etc.)

Importantly, Env.action_space and Env.observation_space are instances of Space, a high-level python class that provides key functions: Space.contains() and Space.sample(). Gymnasium supports a wide range of spaces:

Box: describes bounded space with upper and lower limits of any n-dimensional shape (like continuous control or image pixels).Discrete: describes a discrete space where{0, 1, ..., n-1}are the possible values (like button presses or menu choices).MultiBinary: describes a binary space of any n-dimensional shape (like multiple on/off switches).MultiDiscrete: consists of a series ofDiscreteaction spaces with different numbers of actions in each element.Text: describes a string space with minimum and maximum length.Dict: describes a dictionary of simpler spaces (like our GridWorld example you’ll see later).Tuple: describes a tuple of simple spaces.Graph: describes a mathematical graph (network) with interlinking nodes and edges.Sequence: describes a variable length of simpler space elements.

For example usage of spaces, see their documentation along with utility functions.

Let’s look at some examples:

import gymnasium as gym

# Discrete action space (button presses)

env = gym.make("CartPole-v1")

print(f"Action space: {env.action_space}") # Discrete(2) - left or right

print(f"Sample action: {env.action_space.sample()}") # 0 or 1

# Box observation space (continuous values)

print(f"Observation space: {env.observation_space}") # Box with 4 values

# Box([-4.8, -inf, -0.418, -inf], [4.8, inf, 0.418, inf])

print(f"Sample observation: {env.observation_space.sample()}") # Random valid observation

Modifying the environment¶

Wrappers are a convenient way to modify an existing environment without having to alter the underlying code directly. Think of wrappers like filters or modifiers that change how you interact with an environment. Using wrappers allows you to avoid boilerplate code and make your environment more modular. Wrappers can also be chained to combine their effects.

Most environments created via gymnasium.make() will already be wrapped by default using TimeLimit (stops episodes after a maximum number of steps), OrderEnforcing (ensures proper reset/step order), and PassiveEnvChecker (validates your environment usage).

To wrap an environment, you first initialize a base environment, then pass it along with optional parameters to the wrapper’s constructor:

>>> import gymnasium as gym

>>> from gymnasium.wrappers import FlattenObservation

>>> # Start with a complex observation space

>>> env = gym.make("CarRacing-v3")

>>> env.observation_space.shape

(96, 96, 3) # 96x96 RGB image

>>> # Wrap it to flatten the observation into a 1D array

>>> wrapped_env = FlattenObservation(env)

>>> wrapped_env.observation_space.shape

(27648,) # All pixels in a single array

>>> # This makes it easier to use with some algorithms that expect 1D input

Common wrappers that beginners find useful:

TimeLimit: Issues a truncated signal if a maximum number of timesteps has been exceeded (preventing infinite episodes).ClipAction: Clips any action passed tostepto ensure it’s within the valid action space.RescaleAction: Rescales actions to a different range (useful for algorithms that output actions in [-1, 1] but environment expects [0, 10]).TimeAwareObservation: Adds information about the current timestep to the observation (sometimes helps with learning).

For a full list of implemented wrappers in Gymnasium, see wrappers.

If you have a wrapped environment and want to access the original environment underneath all the layers of wrappers (to manually call a function or change some underlying aspect), you can use the unwrapped attribute. If the environment is already a base environment, unwrapped just returns itself.

>>> wrapped_env

<FlattenObservation<TimeLimit<OrderEnforcing<PassiveEnvChecker<CarRacing<CarRacing-v3>>>>>>

>>> wrapped_env.unwrapped

<gymnasium.envs.box2d.car_racing.CarRacing object at 0x7f04efcb8850>

Common Issues for Beginners¶

Agent Behavior:

Agent performs randomly: That’s expected when using

env.action_space.sample()! Real learning happens when you replace this with an intelligent policyEpisodes end immediately: Check if you’re properly handling the reset between episodes

Common Code Mistakes:

# ❌ Wrong - forgetting to reset

env = gym.make("CartPole-v1")

obs, reward, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(action) # Error!

# ✅ Correct - always reset first

env = gym.make("CartPole-v1")

obs, info = env.reset() # Start properly

obs, reward, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(action) # Now this works

Next Steps¶

Now that you understand the basics, you’re ready to:

Train an actual agent - Replace random actions with intelligence

Create custom environments - Build your own RL problems

Record agent behavior - Save videos and data from training

Speed up training - Use vectorized environments and other optimizations